Press

The Company She Keeps

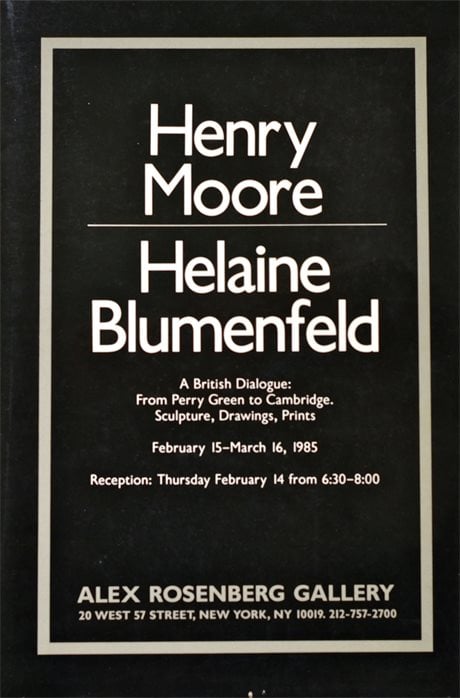

ARTnewsThe show’s title, “A British Dialogue: From Perry Green to Cambridge,” was in fact, something of a misnomer, Henry Moore’s native turf is by now well know, but Helaine Blumenfeld, his coexhibitor at the Alex Rosenberg Gallery in New York recently, turns out to be a born and bred New Yorker, albeit one who has lived in England since 1969.

For the 42-year-old Blumenfeld, the show was something of a homecoming, but she had been less than eager about it at first. “When I was asked if I would show with another sculptor, I said, ‘No; I never have.’” There were further discussions with the gallery, and finally Blumenfeld, “ready to get my guns up,” she says, asked who the other sculptor was. It was Henry Moore. “That stopped me. You can’t really say, ‘I won’t show with Moore.’”

The resultant “dialogue” brought together two sculptors whose abstract forms have much in common but at the same time reveal divergent approaches to the medium. Like Moore, Blumenfeld works in marble and bronze, but many of her sculptures which have separate parts, eschew a fixed base, allowing then to be set in different positions. For Blumenfeld, it’s a way of representing ever-changing human relationships.

“My work is in many ways in opposition to Moore’s,” she says. “It’s another concept of form. I don’t believe in fixed positioning of sculpture. I’m more concerned with sensuality than he is. I really am not trying to portray a natural landscape; I’m trying to express emotion and emotional relationships with an esthetic form. I count on the active participations of whoever’s looking at the sculpture to move it, to change it, to experiment with the form.”

Blumenfeld says she has been particularly influenced by Cycladic sculpture because of the “simplicity of the forms – how much content, emotion and expression can be put into a very simple surface.” She studied with the sculptor Ossip Zadkine in Paris during the mid-1960s (after having earned a doctorate in philosophy from Columbia University at the age of 20). “Zadkine believed you had to be able to work in every material – to carve wood and stone, to work in clay, to do some welding,” she says. “I felt if he had only done wood – that was his fantastic talent – he’d probably be better know than he is. I decided I would learn to carve, but I loved to work in clay. My inspiration is always from clay. It’s not a finished form, it’s not the final solution, but for me, rather than drawing, rather than direct carving in wood or stone, it’s the way I work.”

Only two years after beginning her studies with Zadkine, Blumenfeld was given a one-person show in Paris, and she had another show a year later in Vienna. “I was almost too lucky in the beginning,” she admits. “I wasn’t nearly ready.” In 1969, she and her husband, writer Yorick Blumenfeld, moved to Cambridge. “We both felt we needed to work in intense isolation and went there for what we thought would be a year or so,” she says. They and their two children live there still, although Blumenfeld says she “more or less commutes to Italy,” where she has a studio in Pietrasanta. She shows her work at Leinster Fine Art in London, and has complete public commissions in Oxford and Cambridge and for a federal plaza in Milwaukee.

Since 1980, Blumenfeld has been maintaining another kind of British dialogue as the only American member of the Visual Arts Panel of the Arts Council of Great Britain. Her appointment grew out of a paper, “Where Have All the Standards Gone,” which she was invited to deliver at a conference in 1979. Blumenfeld recalls that she was particularly turned off by an exhibition of “rubbish” at the ICA in London. “I told them that not only did it give the avant-garde a bad name, it gave it a bad smell. The avant-garde was never that person who came from nowhere, but someone who had worked through a tradition and come out of it somewhere else. I was outside the establishment, and most people were afraid to open their mouths. I felt myself totally free; I could say anything I wanted, and I did.”

Within a year, Blumenfeld was appointed to the Arts Council by Secretary General Sir Roy Shaw. “Perhaps he thought it was better to have me on his side,” she says.